Ensemble 13

More Displacement? ... Local Partnerships?

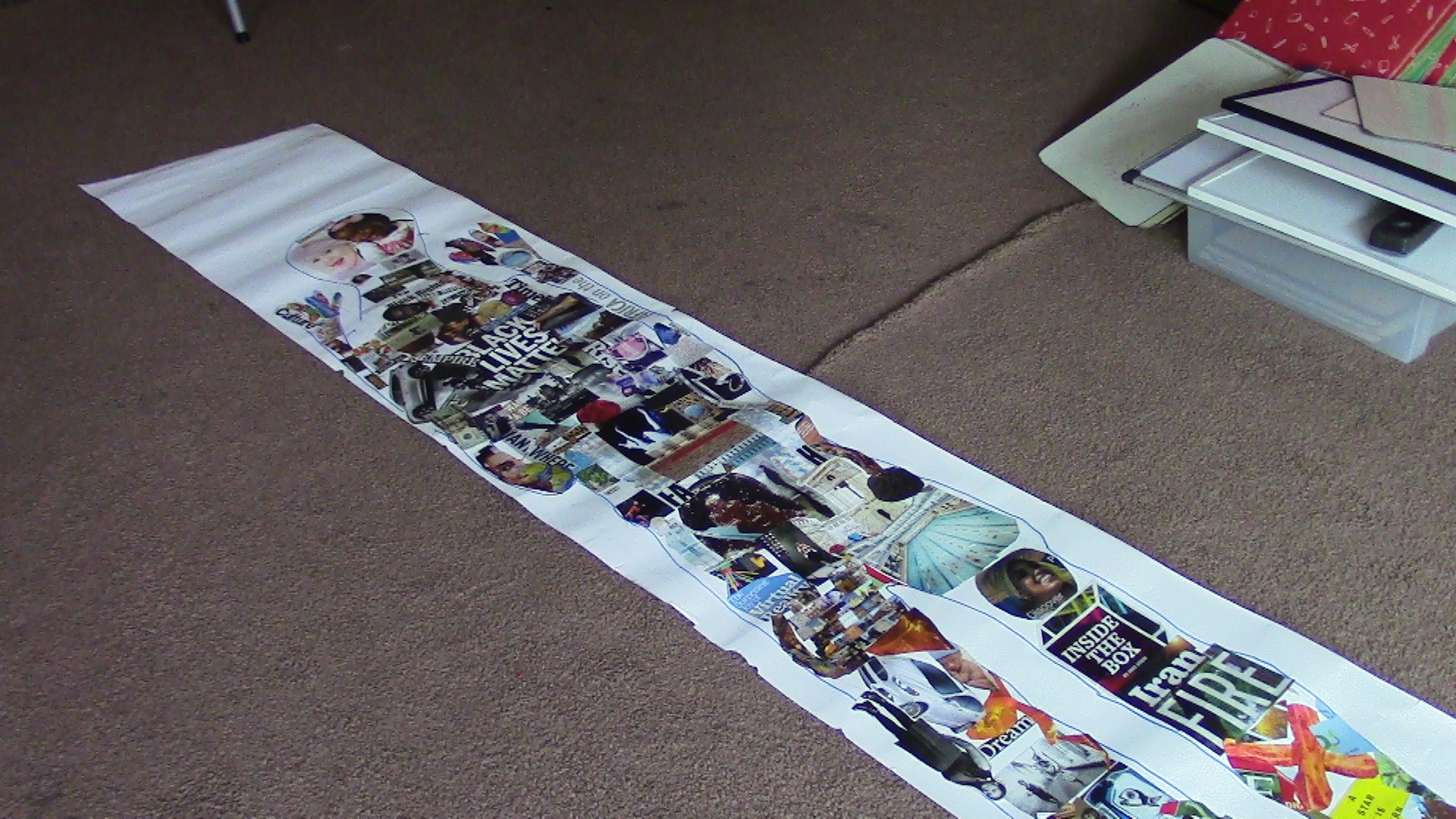

2014-2020

Each drawing: 60"x40"

Tableau: 90"x150"x2.5"

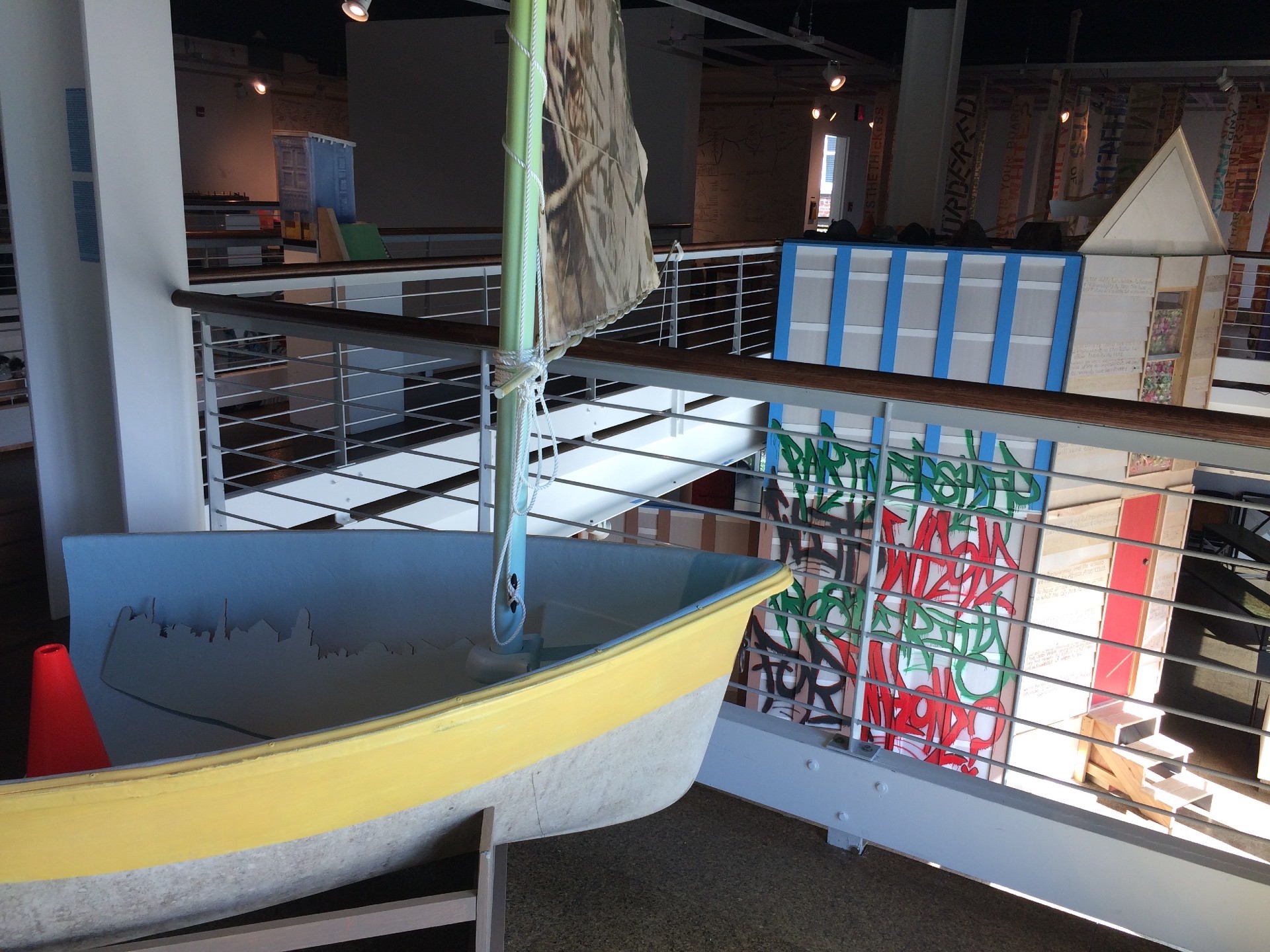

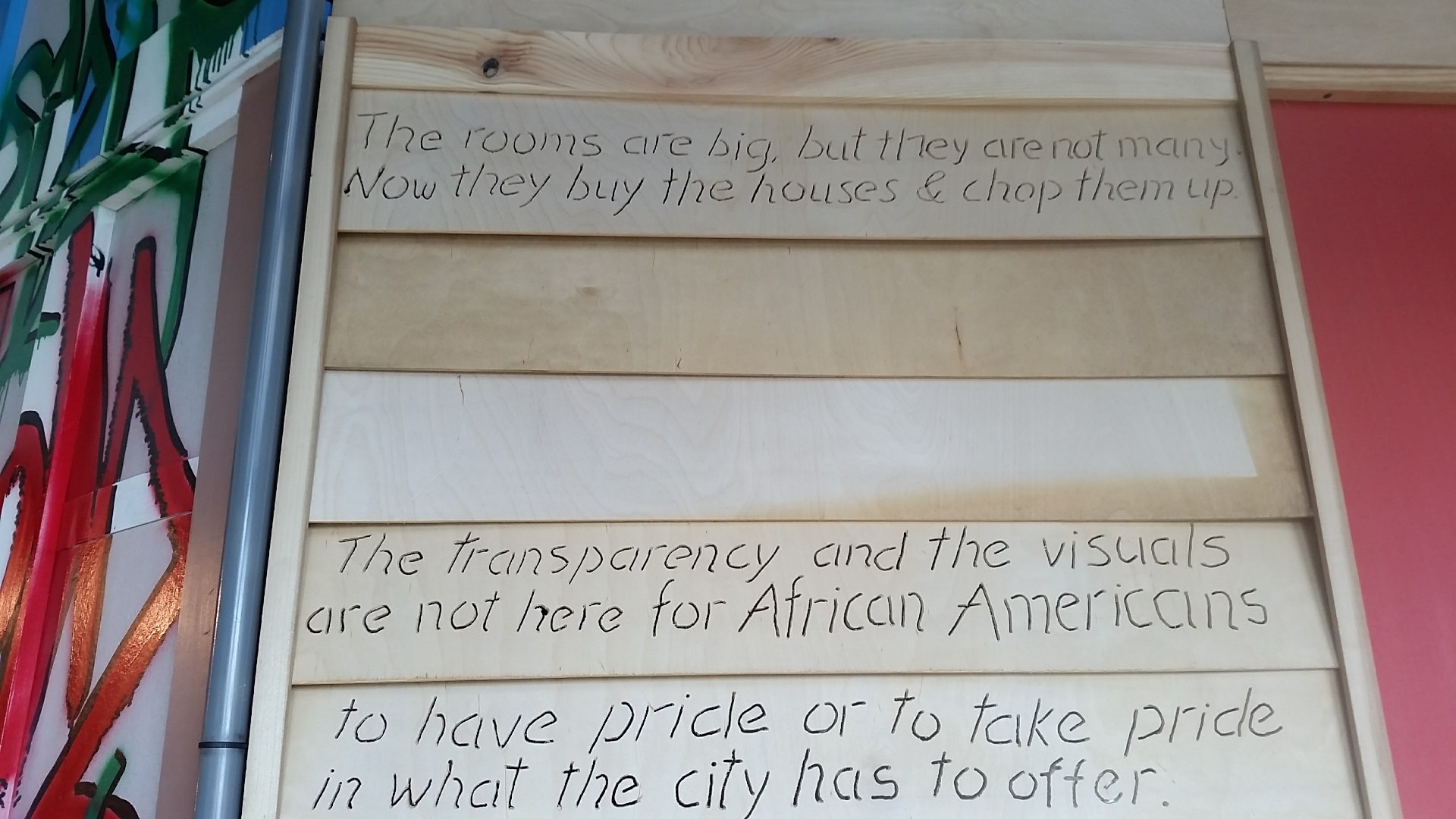

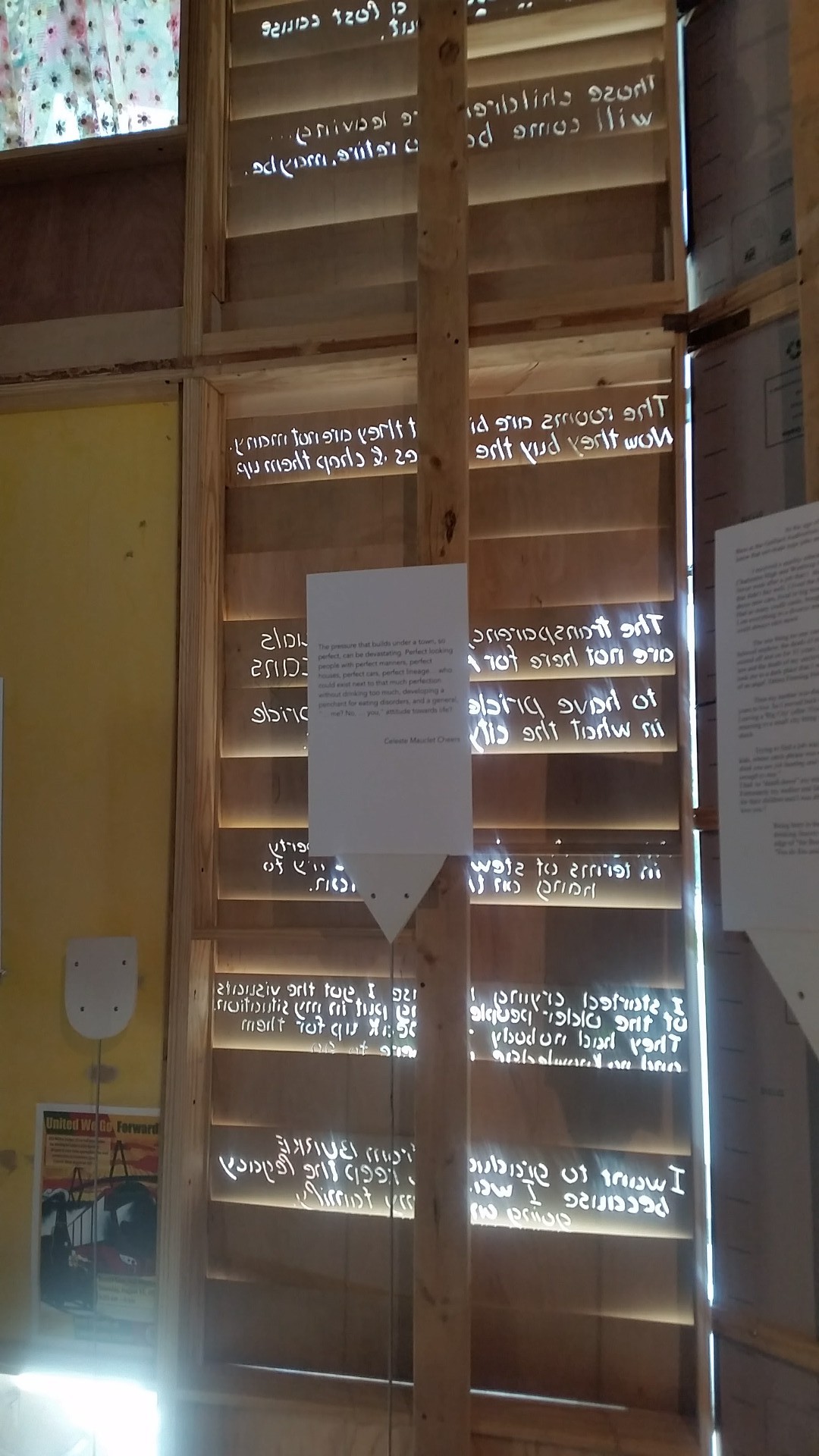

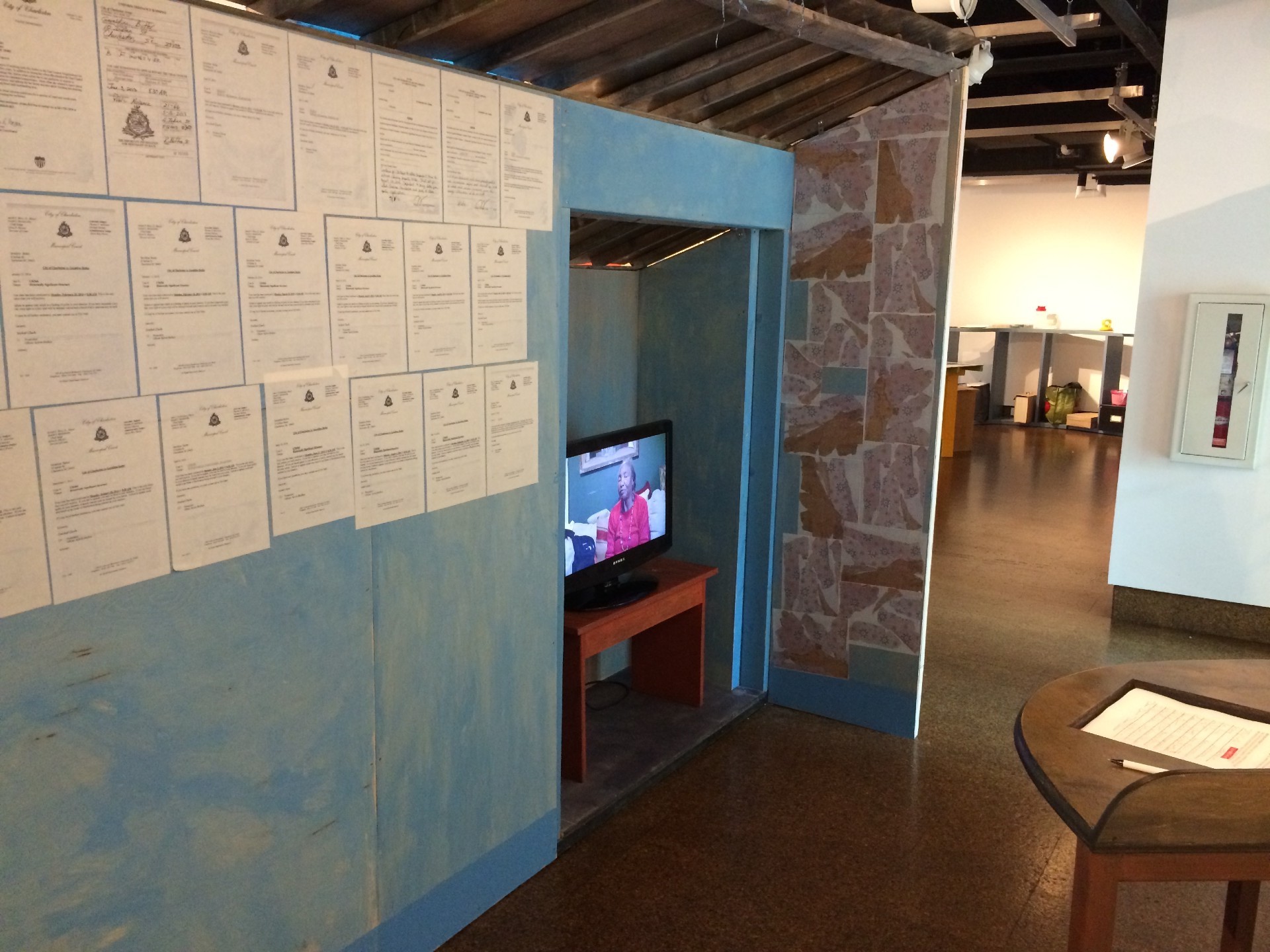

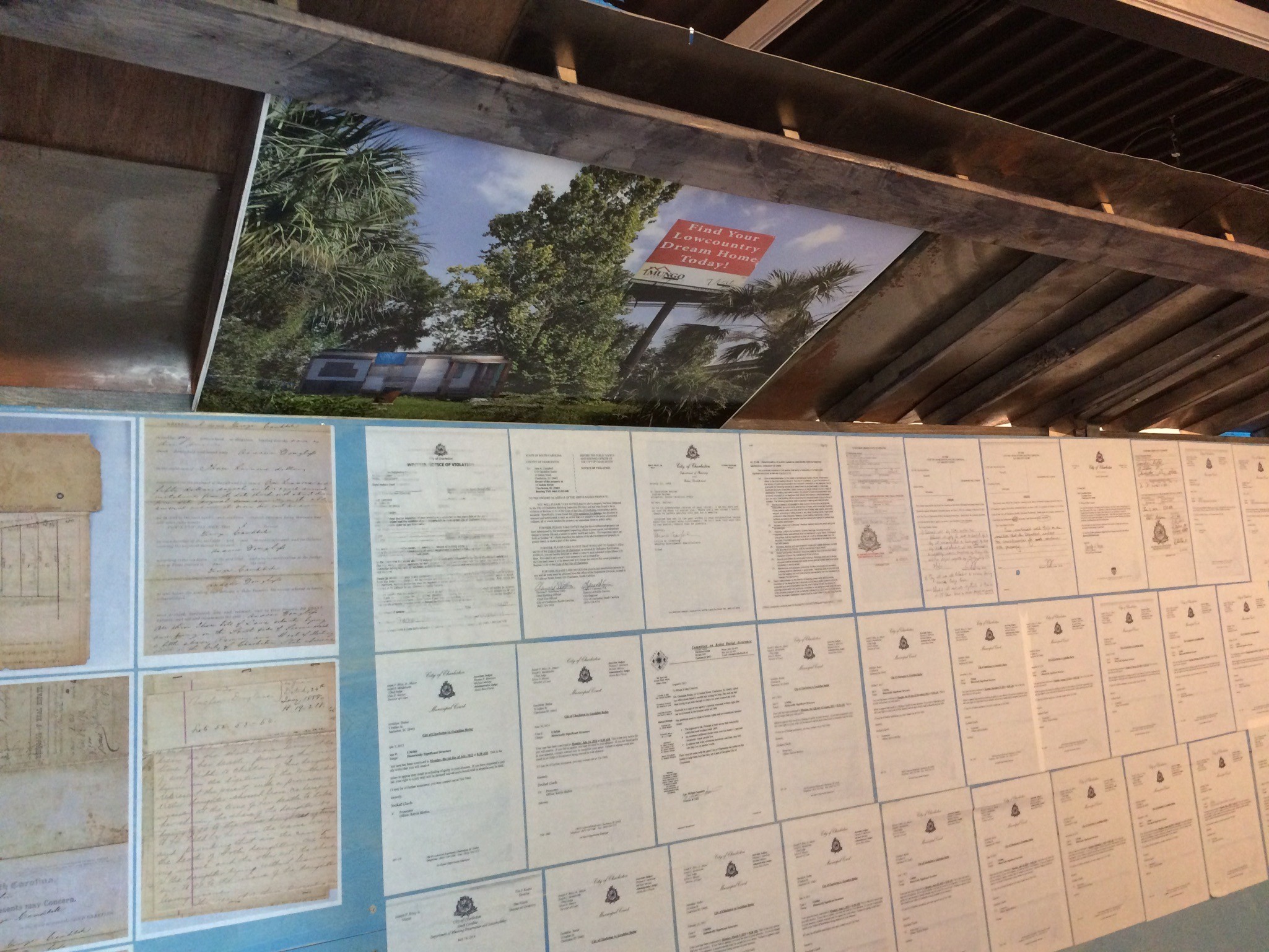

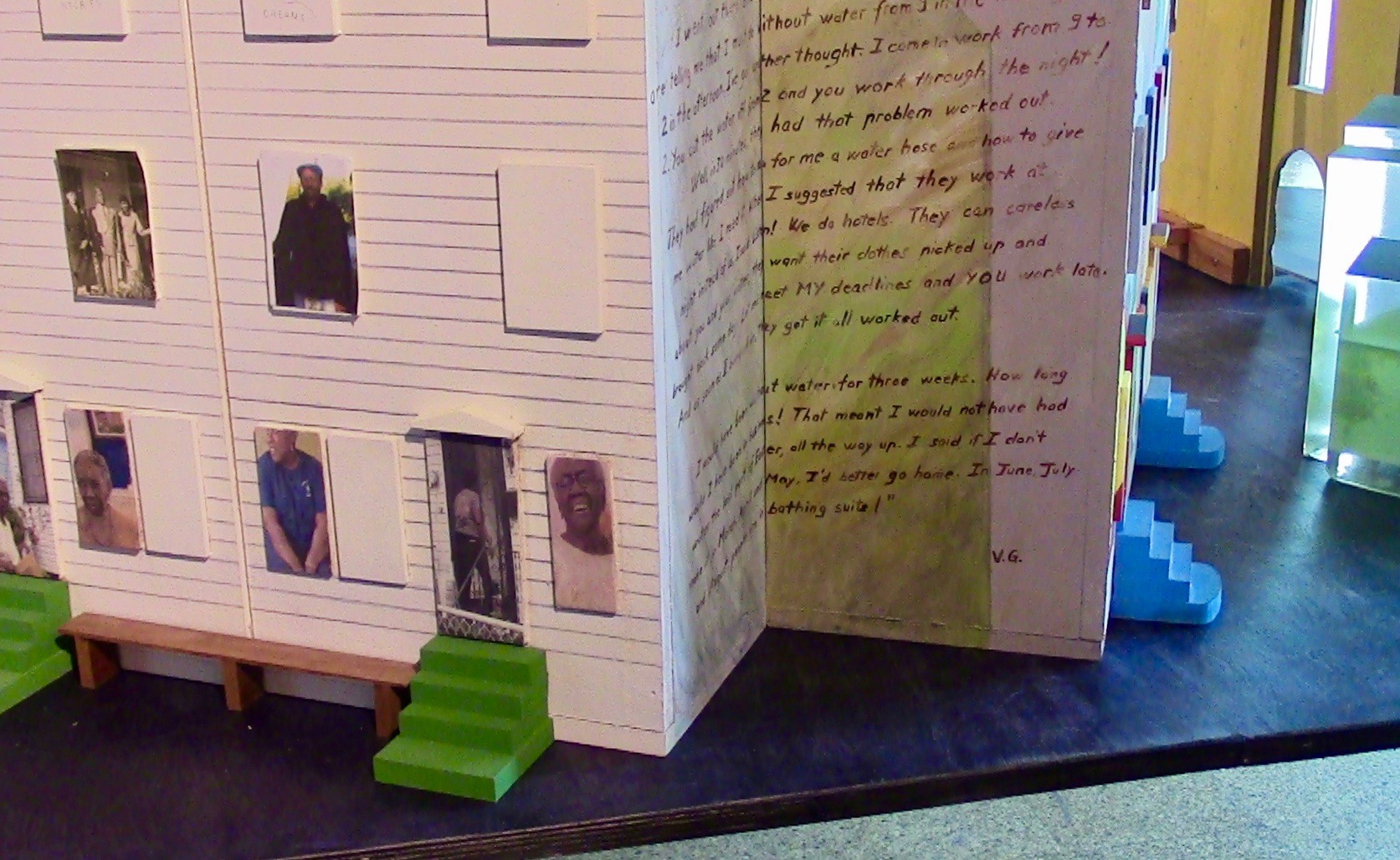

Ensemble 13 highlights boards from the siding of the 16 foot high façade of a “Charleston single” house, built at the City Gallery at Waterfront Park for the art project conNECKted: Imaginings for Truth & Reconciliation. Capscrews keep them separated from the canvases. Texts were carved with the help of conNECKted apprentices. Their authors are African American participants who openly challenge White authorities. Their names are stamped on the boards.

Many more thoughts were expressed during 18 interviews, 12 focused conversations, 8 I-statements and numerous 1mn recordings at the end of each of our meetings.

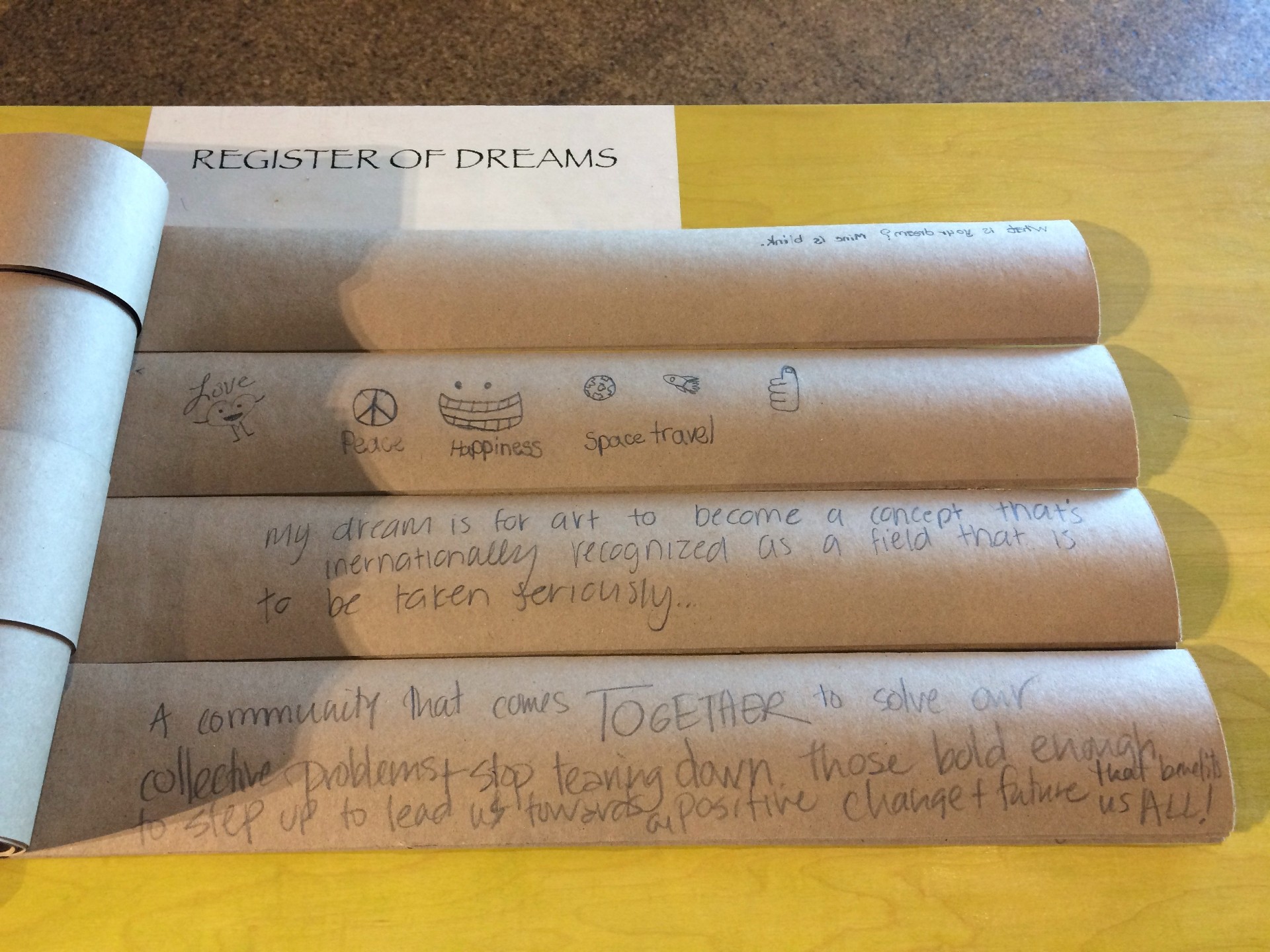

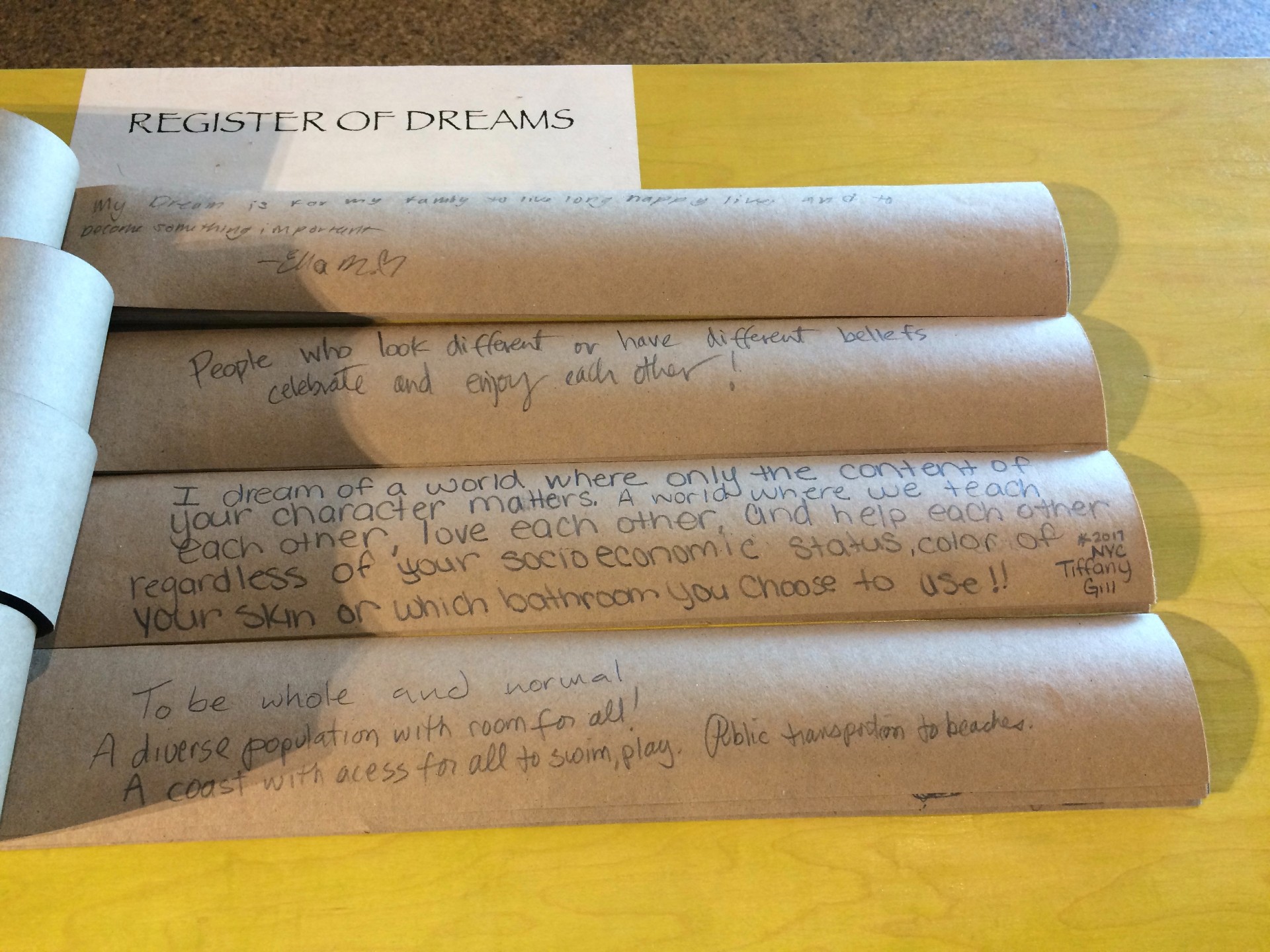

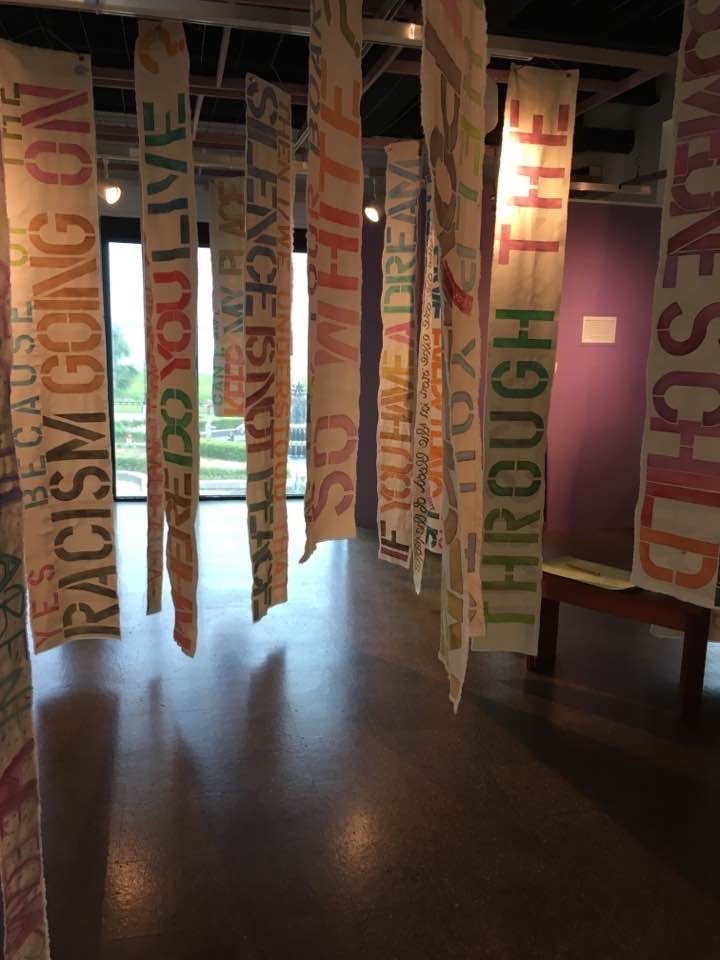

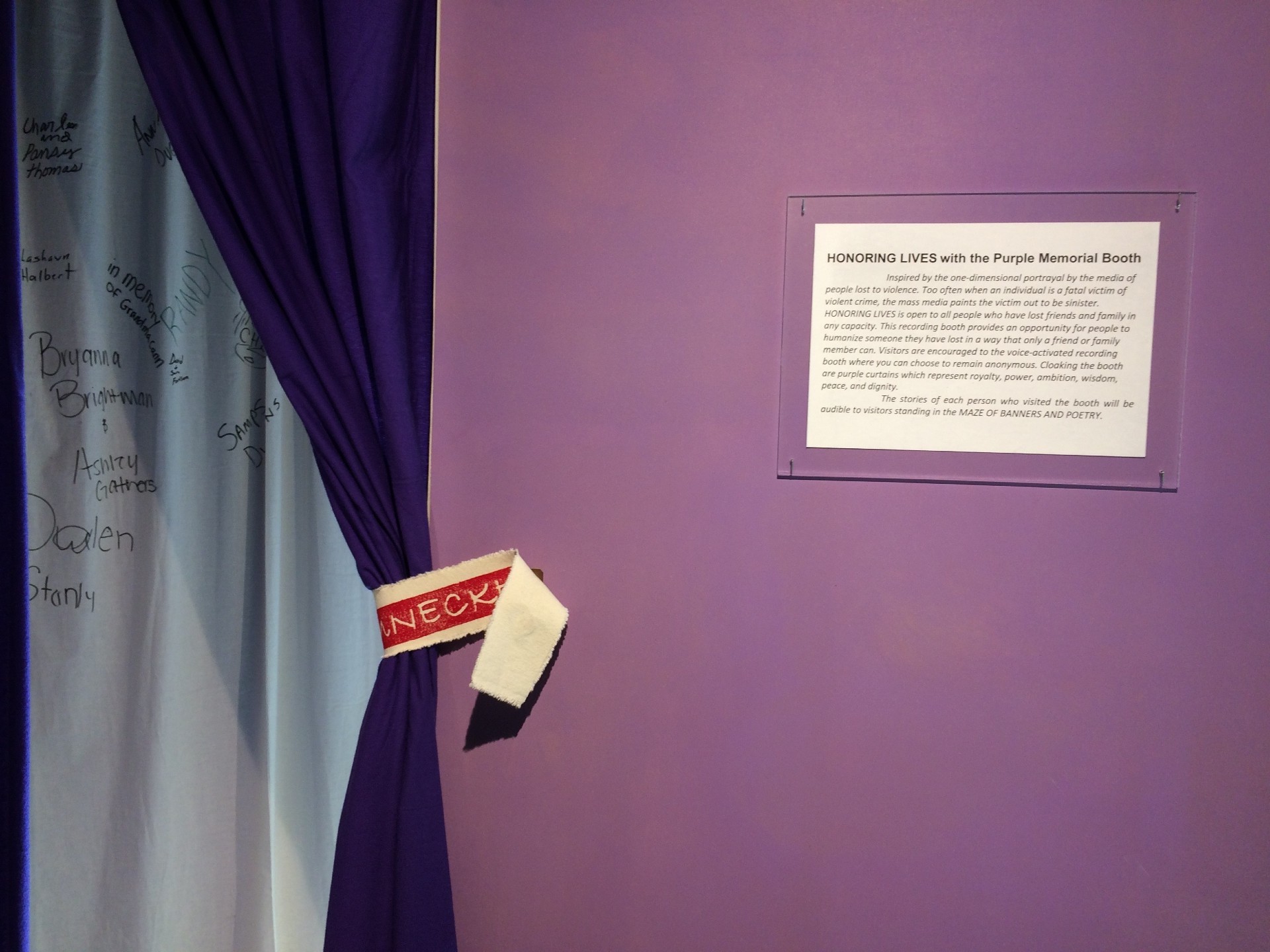

Within the show more was vented in a Book of Grievances and a Register of Dreams; on sticky notes on the Youth Wall; at the Honoring Lives Booth; during the Saturday mornings Question-Relay sessions, and signing three different Petitions.

People wrote and wrote, they were not pushed to write. They also touched, and touched everything, although they were in a pristine gallery space. They were not pushed to touch.

There lie the grassroots voices and the spirit of THE CHARLESTON RHIZOME COLLECTIVE, sprouting from accepting challenges, and the dynamics of collaboration.

Years of attempts … never over … then … conNECKtedTOO … and now … TINYisPOWERFUL … who are we/am I as artist(s)?

A WALLPAPER was printed from 100 handmade postcards carrying the remarks of MLK Day marchers and then sent to Mayor Tecklenburg, one a day for his first 100 days of his first term in office in 2016.

conNECKted: Imaginings for Truth & Reconciliation was a three years adventure (2015-2017). It sought to appeal to multiple audiences by involving them in the conception, the process and the making of the artworks. Charleston City Gallery attendants counted 3,685 visitors. A really good number they said. And many People of Color were part of the count.

Daily records show that the least attended gatherings were the ones which proposed conversations between Artists and Activists. What did we do wrong? There seems to be a cultural misconception, around very easily coded words like Artists and Activists or Art and Activism. And could the historical/touristic nature of the neighborhood be the reason? Or …

. Is it still very hard for artists to get out of the traditional European framing of the visual arts that has been challenged so strongly since World War Two, and before as well?

. Is it still very hard for activists to not see artists as only publicists of their cause?

Will Hamilton with Best Friends of Lowcountry Transit was a remarkable exception.

Three PETITIONS were initiated and sent to the County and City Councils.

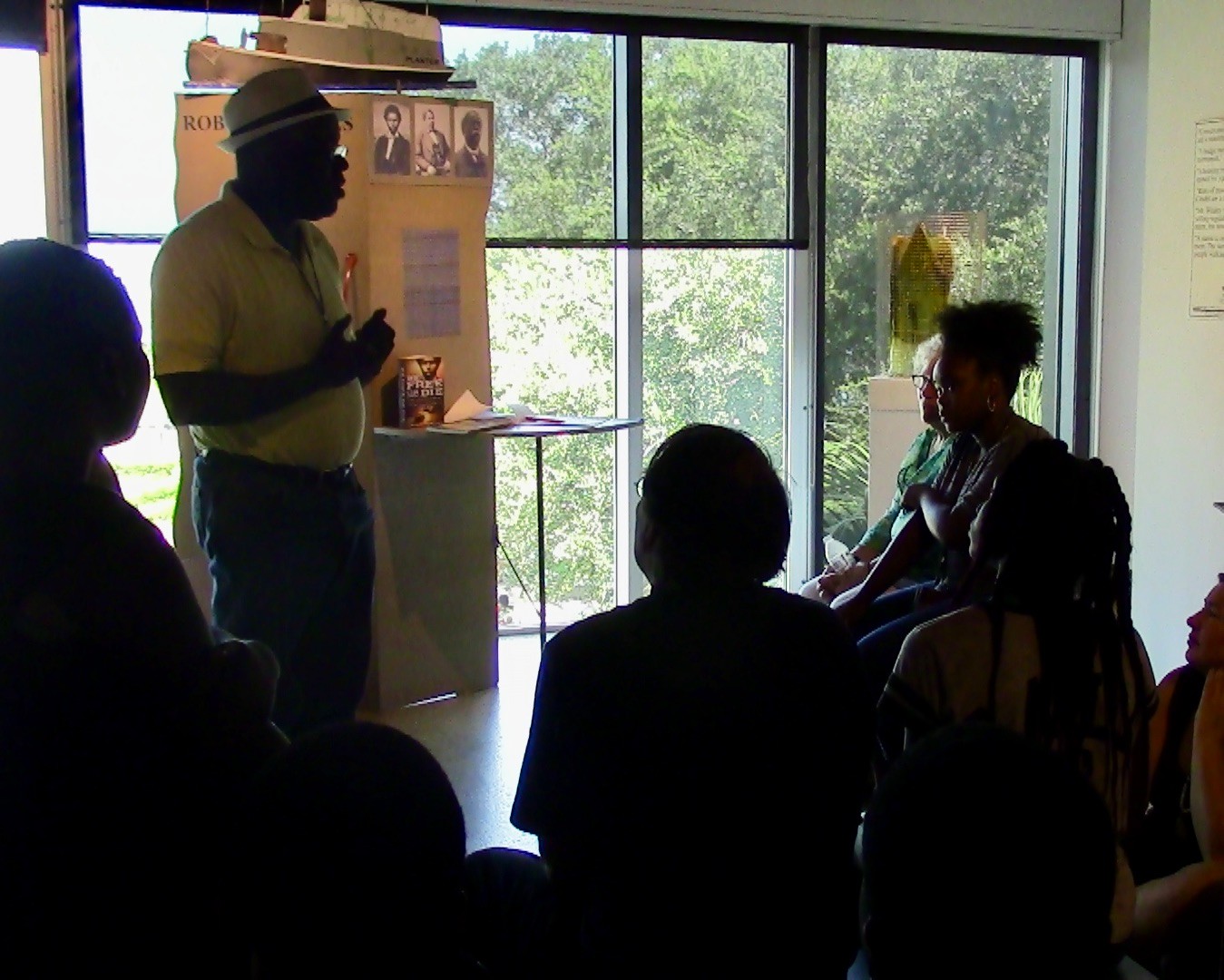

The ROBERT SMALLS petition encouraged citizens to be responsible for writing their own history, lest they lose their sense of history, identity, belonging … and not let substitute academics or luminaries write it for them (see Ensemble 11).

The GERALDINE BUTLER petition called for justice, as a fifth generation Charleston citizen experienced strong pressures to abandon a large piece of her family property and history.

The CULTURAL IMPACT petition proposed a requirement for developers and institutions to be more aware of the cultural damage they do to Charleston neighborhoods.

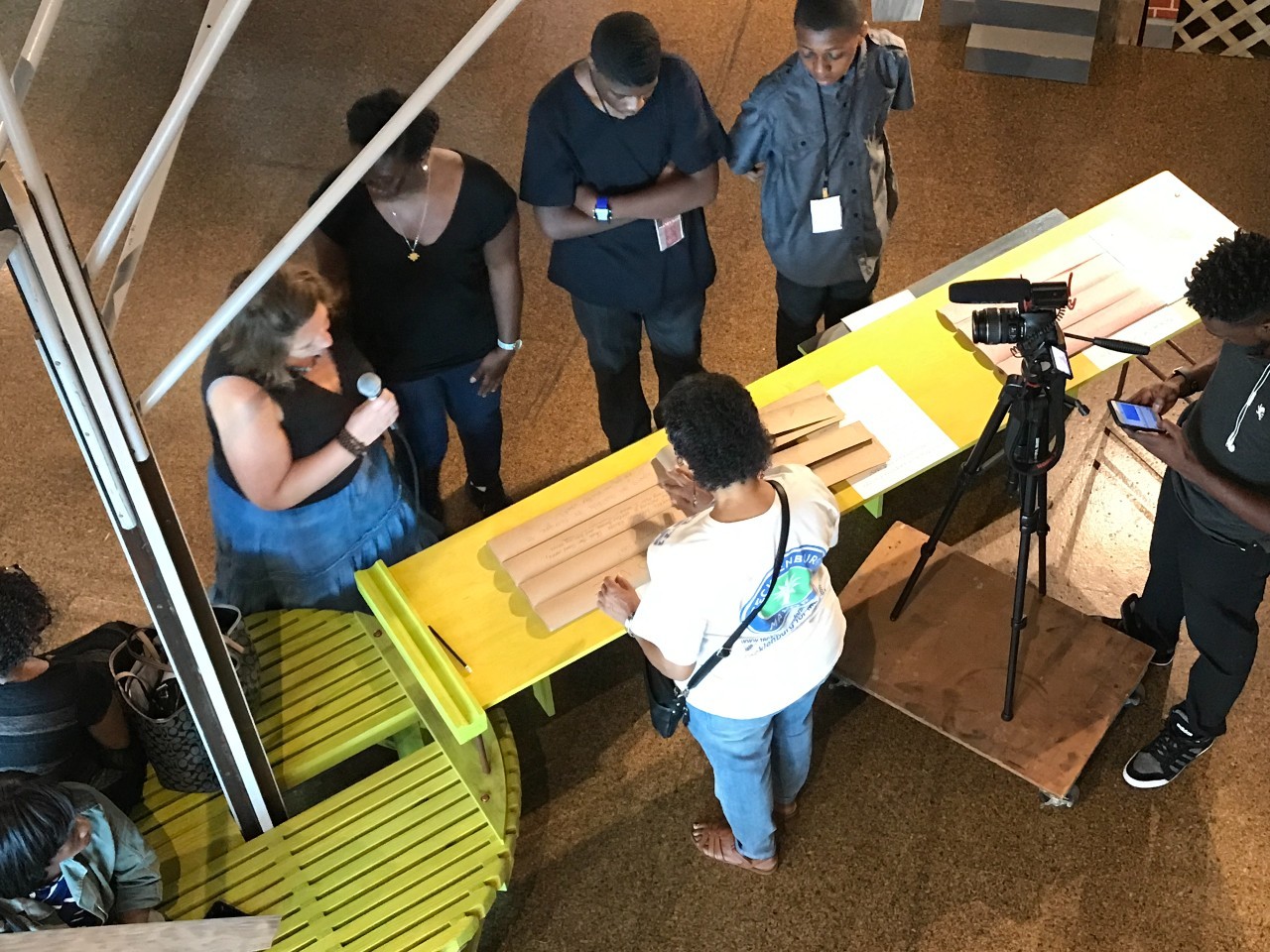

Maps – painted by Kristy Ryba and Sabrina Jeffcoat – cover the “IMAGINATION TABLES” built with apprentices and youth. They combine one map from 2017 and one from the 60’s (before the construction of the Crosstown expressway).

During public sessions the issues above were approached using formats like Questions/Relay, Story Circles, Critical Response that allow inclusive sharing. In their midst we imagined a future for diverse communities in Charleston, strengthening a universal sense of belonging and opening to a future of hope and peace. We call such an enterprise IMAGININGS FOR TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION, “the truth of history and the reconciliation of memories.” ArtSpot Productions from New Orleans, organized two days of workshops

Meandering through a maze of banners (see Ensemble 3), HONORING LIVES Through the Eyes of My Soul: every day a sound device is available to record memories of those no longer with us. They are played back the next day above the maze. Concept by Latonnya Wallace; Recordings management by Bill Carson. The moving sound machine was built in 1978 for the JEMAGWGA sound installation “The Running Dog” and reengineered here by Olivier Rollin.

VIDEOS IN VIEW: “Youth Questions“, “Parents Questions“, “Longing to Belong“, “INTERconNECKtivity“, “Experiencing Gentrification” ,”Mrs Geraldine Butler’s predicament“, “Mosquito Fleet history” with Captain Samuel Joyner. All edited from multiple Interviews. They are now archived at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

The bench was built by J’Mari Butler and Kanar Alexander during the 2016-2017 apprenticeship program.

APPRENTICES Heaven Brisbane, Taylor Dawson, Pierre Gaudin, Kathy Graham, Allen Simmons, Dakevion Henderson, Zaïre McPherson, and Tyeshia Williams engaged in content, fabrication, presentations and docent work.

Other youth participation included PRECIOUS HANDS SUMMER (the group led by Pamella Gibbs, offered its responses to the Charleston Massacre. Students reproduced their original drawings on two canvas banners); JAMES SIMONS MONTESSORI ELEMENTARY (including the Elementary Lower grades for the banners and the Middle School Entrepreneurship class led by teacher Jennifer Savage, which were strongly involved under the leadership of Educator Pamella Gibbs and Artist Gwylene Gallimard); SANDERS CLYDE with “Cityscape” (an urban design program led by Ms Bobo. Built models were installed by La’Sheia Oubre and Debra Holt); MEETING STREET ACADEMY (students under the leadership of La’Sheia Oubre, wrote answers to questions that are often left for adults).

Most interviews were led and recorded by La’Sheia Oubre, Pam Gibbs, Gwylene Gallimard with Auzheal Oubre, Debra Holt, Jason Slade, Jean-Marie Mauclet, Donna Hurt and Latonnya Wallace. We have talked with and recorded Audrey Lisbon, Daly English, Mrs Hicks, Samuel Joyner from the Mosquito Fleet (see a previous bubble about it), Rob Dunlap from the New Mosquito Fleet (a temporary Charleston program) , Mr Backman from Backman Seafood, Barbara Bennett, Viviane Gordon owner of Arrow Cleaner, Vincent German and Gerald Bell, Loquita Jenkins, Charles Maker from Hannibal Kitchen, Geraldine Butler, John Chaplin, Deborah Bobo, Harriett Jenkins Simon with Millicent Brown, Norma Lemon from Island Breeze. Many meetings were recorded as well as shorter interviews with: Jennifer Bremer/Marc Jenkins/Sarah Morrison/Sarah Stewart from Fast & French Inc; Jennifer Saunders of The Stone Soup Collective; Evon Wigfall of the Low-Country Family Support Services; Carlton Turner formerly Executive Director of Alternate ROOTS; Chris Johnson of “Question Bridge” and Damon Fordham, a professor of African-American history.

Therese Shelton, Darryl Wellington, Kimberly Bowman and Celeste Cheers Mauclet offered specific texts. Many thanks to the ASSISTANTS of the “conNECKted” project: Anastatia Ketchen, Sabrina Jeffcoat, Olivier Rollin, Bill Carson and Educator Cara Ernst; to mentor Carlton Turner, now lead artist and co-director of Sipp Culture, ArtSpot Productions from New Orleans, Arlene Goldbard previously of USDAC, Poet Queen Christine, Gary Erwin of Shrimp City Slim, Wim Roefs of If Art Gallery and Will Hamilton of Best Friends of Low Country Transit, for the workshops and performances they led or organized. Most constructions were guided and/or manufactured by Jean-Marie Mauclet with Gwylene Gallimard.